the science of storytelling

Why our brains love a good “because”

There’s a moment every scientist secretly dreads.

You’ve spent years unpicking the behaviour of a molecule, a material, a signal, or a system. You present it, neatly, logically, precisely, and someone smiles politely and says:

“…sorry, can you just explain what that means?”

I suspect that anyone who’s done a PhD and been asked what it’s about is very familiar with this, along with seeing the listener's eyes glaze over as they struggle to maintain understanding beyond the first 2 sentences!

But here’s the twist: it’s not their fault. It’s biology.

Because while we think we’re creatures of logic, we’re actually wired for narrative. Story isn’t the garnish on scientific communication, it’s the delivery mechanism. The solvent in which the ideas dissolve so they can flow into someone else’s mind.

And the more I work across STEM and innovation, the more I realise that story is far from the opposite of science.

Story is how science travels.

So why does storytelling work on such a stubbornly rational species?

Let’s start with something psychologists call narrative transportation, the phenomenon where a well-told story effectively hijacks your brain and pulls you inside it. Green & Brock (2000) showed that when people are “transported”, they become more open to new information, more empathetic to unfamiliar viewpoints, and more likely to remember details long after the moment has passed.

In other words: a good story temporarily lowers the brain’s cognitive drawbridge.

This isn’t magic; it’s chemistry. Stories trigger activity in a constellation of neural networks - memory regions, sensory cortices, language centres, creating what neuroscientist Uri Hasson calls “neural coupling”, where the storyteller’s and listener’s brains start mirroring each other.

If you’ve ever wondered why explaining a concept through analogy (“Imagine the battery as a busy hotel…”) feels instantly easier, that’s why. You’ve given the brain a familiar anchor, a cognitive foothold if you like.

The engineering metaphor would be quite literal here: story increases the coefficient of friction between the idea and the mind.

Why facts alone struggle to stick

One well known bit of research is a 2014 Stanford experiment where two groups had to convey a set of ideas: one using stats, one using stories. The story group achieved rememberability levels up to 22 times higher. That’s a staggering difference (which to be honest does need a bit of digging to substantiate, but have a look in the references to hear it from Jennifer Aaker.)

It’s not because stories are “simpler”, I find that scientists hate that word anyway, but because they provide what psychologist Jerome Bruner described as “a map of possible human experience.”

A statistic tells you what happened. A story helps you understand why it matters.

This is especially important in science communication, where we often ask people to grasp invisible processes, non-intuitive behaviours, or counter-common-sense mechanisms. A narrative supplies the missing structure - a cause, an effect, a bit of tension, maybe a dash of uncertainty — and suddenly the concept gains momentum.

The shape of a story, and why scientists should care

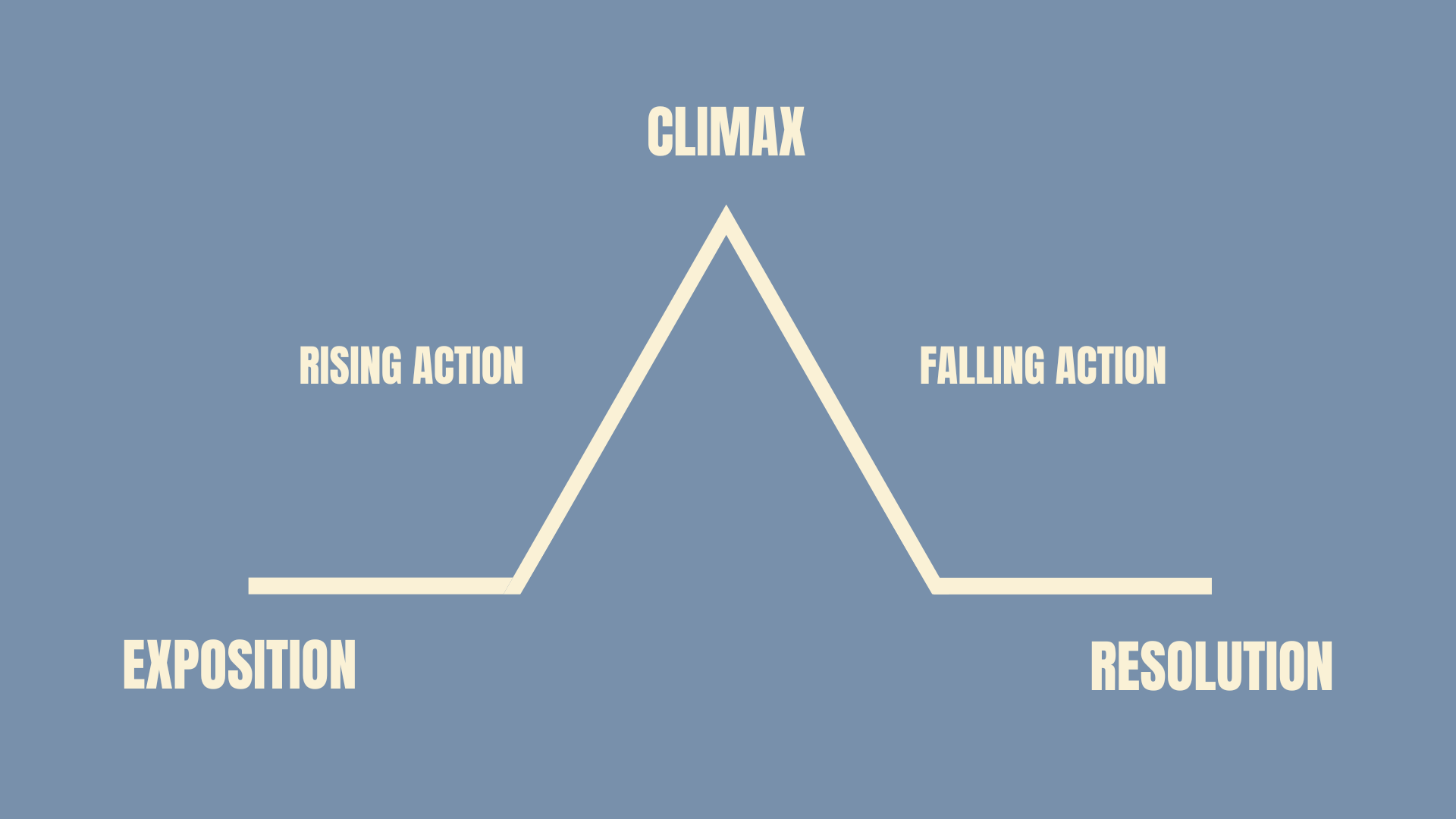

Story structures aren’t just creative fluff; they reflect deep cognitive patterns.

Take Freytag’s Pyramid — the classic rise → complication → climax → resolution. Swap the labels and you basically have the shape of most scientific papers:

Status quo → what we already know

Inciting problem → the gap in understanding

Rising action → experiments and analysis

Climax → the discovery

Resolution → implications and next steps

There’s a reason this structure keeps evolving back into our work: it aligns with the way humans seek meaning. We’re constantly asking:

What changed?

Why did it change?

What does that mean for me?

A well-structured scientific story answers all three.

Stories carry emotion, but not the way marketers think

Scientists often wince at the word “emotion”, as if it implies melodrama or manipulation. But in communication science, “emotion” usually means salience, the degree to which information feels relevant enough to store.

Fear, curiosity, confusion, delight, surprise… these are not embellishments; they are switches in the memory-encoding system.

There’s a study from Fiske & Taylor (1991) on cognitive miser theory showing that humans conserve mental energy by selectively engaging deeper processing only when something feels personally significant. Story, with its built-in uncertainty, stakes, and patterns, is an efficient way to signal: this is worth your time.

It’s not about making science theatrical. It’s about making it noticeable.

Even a hint of narrative tension (“The model predicted X… but the material stubbornly refused to cooperate”) acts as an attentional Velcro strip.

But here’s the catch: storytelling in STEM must obey the physics of truth

Science communication isn’t Hollywood. You can’t bend the arc to suit the message. You can’t exaggerate the stakes. You can’t sand away the uncertainty.

But you can, and should, arrange the information in a way the brain naturally absorbs.

A good scientific story doesn’t distort; it clarifies. It guides attention. It connects dots that already exist but aren’t yet visible to the untrained eye.

The power isn’t in invention; it’s in illumination.

A practical storytelling framework for scientists (that won’t make anyone feel “too marketing-y”)

Over the years, working across the STEM sector, I’ve ended up using a simple three-part structure, which is fundamentally the classic 3 part structure of film and theatre: Act 1 - Setup, Act 2 - Confrontation, Act 3 - Resolution.

It goes like this:

1. The Known

Start with what your audience already understands — a behaviour, a pain point, a misconception, a curiosity. Anchor the concept in familiar territory.

2. The Tension or Problem

Introduce the unexpected twist — the part of reality that doesn’t behave the way intuition expects, or the thing that needs solving to move everything forward. This is your narrative voltage difference. The bit that gets the neurons paying attention.

3. The Reveal

Show how the science resolves the tension. The mechanism. The insight. The solution. The elegant explanation they didn’t see coming.

This is of course a little simplistic, but it does give a useful start point to telling a story in a way that your audience can connect with.

I think this is a nice example, the 5G SWaP-C Project that we filmed with Space Forge, Compound Semiconductor Applications (CSA) Catapult and BT Group.

It frames the problem, explores the science, and then, I hope, leaves our audience understanding a bit more the topic than they did before.

Why storytelling isn’t a soft skill — it’s an essential scientific one

At its core, storytelling in science is about empathy: meeting people where they are, not where you wish they were. It’s about reducing cognitive load so complex ideas can travel further, faster, and with fewer casualties along the way.

And honestly, it’s about respect. If we want people to understand new technologies, trust emerging systems, or appreciate the wonder behind the equation, then the least we can do is deliver the information in a format their brains evolved to decode.

Story is not the enemy of rigour. It’s the interface layer.

And in a world where innovation is accelerating faster than most people can comfortably process, that interface has never been more important.

So what stories are you trying to tell next?

Because somewhere in your work — buried under graphs, datasets, or simulation logs — is a narrative arc waiting to be uncovered. A tension begging to be resolved. A moment of scientific drama that could help someone finally “get it”.

And if we can turn more of those hidden arcs into open doors, maybe more of the world will walk through.

If we can “zoom out”, rather than focus on the minutiae that is our scientific inclination, then the story can be easier to find.

Curious to hear: what scientific story have you struggled to explain, and what finally made it click?

References

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Hasson, U., Ghazanfar, A.A., Galantucci, B., Garrod, S., & Keysers, C. (2012). Brain-to-brain coupling: A mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.007

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343711

Stanford “Story vs. Statistics” Memory Study (often attributed to Jennifer Aaker’s research group). (Note: The “22x more memorable” figure is widely cited in behavioural comms literature; it stems from analyses within Stanford’s strategic communication teaching materials.) https://womensleadership.stanford.edu/resources/voice-influence/harnessing-power-stories

Freytag, G. (1863/1894). Freytag’s Technique of the Drama. Public domain text available here: https://archive.org/details/freytagstechniqu00freyuoft

Cognitive Miser Theory summary: Fiske & Taylor's foundational overview:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_miser#:~:text=In%20psychology%2C%20the%20human%20mind,as%20economics%20and%20political%20science.